Squad Leader, 1st of the 46th, 196 Infantry Brigade, Americal Division Vietnam 1969-70

I had just been hired by the US government. The government told me that my job might be anything, but I knew where I was headed. I was going to Vietnam. I was going to kill my nation’s enemies. I was vulnerable to this invitation to join the government payroll because I had just completed undergraduate school. I was now 1A (status: eligible). Nixon had just been elected President on the promise to end the war. I did not want to go to Vietnam. I particularly did not want to kill people although at the time I really didn’t understand the full implications of taking someone’s life. During training, I spent every available moment in base libraries searching for news that Nixon had ended the war. As the days passed with no news, I began to think about deserting, going to Canada. I was already in the Army. If I went to Canada, I would not be a draft dodger, but a deserter. That was serious. If I deserted, I was certain I would never be able to enter my home again. But Vietnam was not my cause. I was not even sure what the cause was. I had seen film of our truly revered President Eisenhower talk about the domino effect. Once Vietnam fell, all of Southeast Asia would become Communist. If Southeast Asia became Communist, India with its billions of people would fall and so on. I was not convinced. I was also not sure how the whole mess in Vietnam started. I also wondered at the difficulty the US was having stopping our part in the fighting. I had read that just before his assassination, President Kennedy had ordered our few troops out of Southeast Asia. The first thing the new President Johnson had done was to reverse this order. This did not fill me with confidence that Nixon would bring an end to things by increasing the bombing. Ultimately, I went to war.

I left from Ft. Lewis. Wet snow covered the ground. The temperature was about 35 degrees. The plane had regular seats, but there were no windows. I was scared. Even though most of us would never see any violence, we were all scared. There was no preparation. No First Sergeant stood in front of us to tell us where we were going (specifically where we were going; everyone knew we were going to Vietnam.) Nor was there anyone to tell us what to expect when we got there. Twenty-two hours later, after spending what seemed like an absolute eternity in a darkened tube, we landed. We had landed at Cam Ranh Bay. It was a huge base. On one side was the Pacific. Surrounding the base on the land side was a perimeter manned by a Battalion of Army grunts. The most of the war this base saw was the occasional mortar round fired from an ingenious VC mortar team that managed to come within range despite the Battalion of Infantry attempting to keep them at a distance.

When I stepped from the plane, a blast of heat and humidity struck me in the face. It was October, but it was hot and very humid. I was ordered to a barracks loaded with bunk beds, mattresses rolled in two, no sheets, no pillow. I was exhausted. The next afternoon, I boarded an Army plane for Chu Lai, my Division Headquarters. I spent two weeks there learning the only information of value I had received in the year I had been in Army schools. We were given classes on booby traps. Each area had its unique booby trap designs. We were given lectures by Chu Hoys – North Vietnamese Army Regulars who have surrendered to work for the Americans. During this two-week orientation, I stood the first realistic guard duty of my short service career. We did not know that we were ring five in a series of perimeters guarding the base. I was now in “Indian Country.” This was where the NVA (North Vietnamese Army) owned the countryside.

I went to my Battalion LZ in a chopper, a supply Huey. It was a long flight. We were at about 5,000 feet to protect ourselves from 51 caliber machine guns and rifle propelled grenades (RPGs). The climb from the helipad to the bunker line and LZ perimeter was a long, vertical thousand feet. I checked in, rifle and pack in hand to be assigned to 1st Platoon, Bravo Company. Two weeks before, Bravo Company had been hit hard. 1st Platoon had lost its Lieutenant and several squad leaders. I was here to replace one of the squad leaders. The platoon would be on “the Hill” in a couple of days. I waited. I met no one. I read when there was light. I had been given a tiny bunker all to myself. Nights were tough. I was never sure what to expect. I waited for the Hill to be hit by sappers or mortar rounds. I was getting used to the constant tension. It never went away, but it did not dominate my every thought either as it had.

The Platoon arrived. They were shaken. They were physically spent. The platoon was given three days to heal from immersion foot, sores, sleep deprivation. Then they – we – would move out for another 30 day mission. I was called to a meeting the night the Platoon returned. I was given a squad, a rifle squad. When we walked off the Hill, I would have three other guys and me: Terry Moreland from Salem, Tom Baney from Ft. Wayne and John Seabaugh from Cape Girardeau. I remember Terry picking a land leach off my neck at the base of the Hill as we walked off. That was the beginning of a true hatred of land leaches. They were everywhere in the field, high and low bracing their bodies waving in the air feeling our heat, coming for us, mounting us sometimes three on top of each other. Ten, twenty, thirty at a time on a bad day, each leach injecting its own brand of coumadin. The blood flowed. Infections set in. I grew to hate them.

My first mission was not a good one for me. The Battalion’s area of operation (AO) was a free fire zone. Anyone in the area who did not wear OD green was the enemy. We were to either kill or extract them. Our area extended from Central Vietnam to Laos. The platoon walked west for four or five uneventful days. About 10:00 one morning, we hit a small village. There were NVA there. The NVA also had their families – woman, children, elderly. We were spotted. An AK47 opened up. Game on.

I was so new. Three weeks earlier, my new wife and I were in San Francisco attending the stage play “Hair.” Now I stood in the midst of hell. The most prominent structure in the village was a large bamboo building. Several NVA were firing from the structure. Big Mike, an M60 machine gunner, was standing John Wayne style in the middle of an abandon rice paddy without

cover firing from his hip pouring death into the hutch. Seabaugh fired an M79 white 3 phosphorous grenade into the hutch setting it ablaze. A man appeared on fire. He stumbled still on fire. Someone I did not know came up behind him putting three or four M16 rounds in his back and buttocks, the rounds reemerging out his shoulder and side. In ten minutes, we had

swept the village. There was a hole somewhere near the center of the cluster, a tunnel. Grenades were tossed in. It was a large hole. A couple of guys jumped in (I thought they were absolutely fearless.) An old man was yanked out, naked, blood dripping from both ears. I learned latter that the grenades had been percussion grenades. Then a young boy was pulled out also naked, but dead. He was perhaps 10 years old. Others followed. Some dead. I wept. I could not stop crying. I was ashamed of being seen crying, but I was also frightened to find a private place for fear I might be found by the NVA and shot. I might be killed on my first mission while weeping.

There really was not time for any of this. Mortar rounds began coming into the village. Clearly the accuracy of the rounds was an indication that this event, the overrunning of the village, had been anticipated. The rounds were spot on. We gathered those villagers remaining and left.

I made it through the critical first month. Baney taught me the ropes. Then he was transferred to another squad. Seabaugh finally warmed up to me. Terry looked after me as he looked after everyone who came within his scope. Others came. I had Bronze Star recipient. I had one Silver Star recipient. He was a wonderfully unlikely farm boy from Davenport, Iowa. All of us but Baney had a Purple Heart. One of us had four. This is not the kind of notoriety one wants although forty years later, they look impressive in a shadow box. I did come to some terms with what I was doing. I loved these guys. I did my best to be kind in the midst of the brutality. But there were problems.

R and R was one of those problems. I was to meet Bonnie, my wife, in Hawaii. Bon had spent the past five months in Australia totally oblivious to what was happening a thousand miles north of her. She was waiting for me in Honolulu when my plane touched down. I was skinny, pockmarked with sores having done battle with my daily enemy. The GI’s were to walk through a gantlet of wives awaiting their husbands. Bon never mentioned it, but I bet each of us, even those assigned to the rear, looked very different. I was emotionally stiff and shut down. I was not feeling well. I was not feeling anything. We found one another, kissed, went back to the hotel, made love – all stiffly. I had brought a couple of high quality Ship to Shore radios taken from dead NVA for shipment back to the States, back to the World. I showed Bon asking her to mail them when we parted. They smelled so strongly of Vietnam, of strange wood smoke and Asia. I hadn’t noticed until we opened them in that room. I watched Bonnie withdraw. She looked at my body many pounds lighter, covered with foreign marks and knew that I had been someplace very different. To make matters worse, in a few hours, I would be returning. Despite all of that, Bonnie has fond memories of our time together. I have indifferent ones. It was not because I did not love the air she breathed. There was part of me missing. When I boarded the plane to return to my guys, I wept uncontrollably. I did so without self-consciousness. I had earned my stripes. To hell with them. Anyway, I was not the only one crying.

I made it through to come home to Bonnie. Almost all of us came out within a few days of each other, all of us ending up in a hospital in Japan. Baney was left as was Seabaugh and Moreland. Moreland was killed two days after I left the field. Surrounded, he was killed charging a line of NVA. Terry took two in the chest, a tight shot group heart high. He was dead before his leg finished swinging. Through all that, he was the only one in the squad who died. I was not there by his side. Most of us were not there. He was left with strangers. I loved him so much.

That was many years ago. My wife and I are still together. We have raised two sons. We have built a good life. I brought much back from Vietnam. For the most part, that stuff lay dormant while I provided a living for my family. More recently it has reemerged. It is good that it has. There was a deadness in me all of those years, a disconnect. I struggled to relate to other’s problems. I had this dead zone. I thought it was natural. More recently anger has come and dreams, difficult dreams. I struggle with leadership that begins wars on a whim having no idea the cost. I guess I am entitled to that anger. I am involved with our young men returning from the wars in the Middle East. I am involved with the mothers and fathers of those who have not returned. I am very much a pacifist.

But not all of my combat Company is pacifist. Every year, there is a Company reunion. Most of those guys remain hawks. Those that are more like me are the ones who went to the deep woods upon returning. We do not see them much. For some, the war still goes on.

]]>

…Some of them died.

Some of them were not allowed to.

—Bruce Weigl, “Elegy”

The Band recorded the song “The Weight” in 1968. I arrived in Vietnam that same year and left in late 1969. I spent most of my tour with Hotel Company, 2nd Battalion, 7th Marines as a platoon commander in the bush. I first heard the song while I was still in country. Although it’s full significance didn’t sink in right away, “The Weight” struck me even then as yet another metaphor for the war. Gradually it would dawn on me that the song is about laying down burdens, and it appeared we were going to have a lot to learn about that. But, this would all come much later.

When I came home, I assumed I would just move on. I got married, went back to school, got a job, had kids, and did the other things that seemed normal. I had been back fifteen years when my family and I made our first visit to The Wall. It may have actually been the first real step home from Vietnam, but it was going to take a while to grasp the weight of that.

The Wall has helped to heal a lot of people. It has quite literally become the touchstone for veterans and families alike. Alone, however, there’s only so much The Wall can do. This became clear to me recently when I came across a remembrance posted on the VVMF website. It talked about a Marine’s experience during a firefight on the night of August 29, 1969. Two of his friends, PFC Louis Vincent Hermann, Jr. and PFC Gerald Allen Smith, were killed that night when their unit was ambushed by the NVA. On the same night, Hotel Company was also in contact with the NVA. We had several people down including 2nd Lieutenant Michael Patrick Quinn. Mike and his team were cut off from the rest of the company, and for a while, we were unable to reach them. The two Marines were with Golf Company 2/7 and were on their way to help us recover our dead and wounded. They probably died almost within shouting distance of us. I never knew this until now.

I’m at once grateful and sad to finally learn their story; grateful to know that their sacrifice won’t go unrecognized, but sad that it has taken over forty years to find out about it. I wonder too whether the families know of the circumstances surrounding their deaths. And, for that matter, do the families of their surviving comrades know what they went through that night. I suspect not because I doubt any of them have ever talked much about it.

This is just one story that emphasizes the significance of sharing these memories and keeping them alive. There are many more of them. Soon the Education Center at The Wall will begin doing what The Wall can’t; bringing stories like this home before we lose them. The dedicated people at VVMF are working hard to collect these stories. Unfortunately, considering the age of the average Vietnam vet, there is limited time left for this to happen. VVMF has undertaken a mission that amounts to a sacred trust; not unlike the trust that existed between veterans in Vietnam. And, they are going to need some help from us to complete their mission.

When veterans returned from Vietnam, there wasn’t much incentive to talk about our experiences. Given the cultural and political climate at the time, we just wanted to put it behind us. That, of course, wasn’t so easy to do. As time has passed, I think a lot of veterans have attempted to open up but found it more difficult than they expected. This probably goes way beyond just not wanting to relive painful experiences. I suspect we’ve all found that, whether we talk about it or not, that part doesn’t go away. I think we just don’t know how to talk about it.

When we do try and talk about Vietnam, the results may not always be as helpful as we’d hoped. Over the past few years, guys I haven’t heard from since leaving Vietnam have started calling or emailing to talk about our experiences. It’s been great to reconnect, but what’s been a bit unsettling about these conversations is that they tend to deal more with the logistics and chronology of things than with how we felt then, or feel now, about them. For example, near the end of my tour, we landed in a hot LZ on Hill 953 in the Que Son Mountains. The area was occupied by elements of an NVA division. We took casualties during the landing, but due to weather and heavy ground-fire, the LZ was closed before we could get our medivacs out. It took us five days to walk down off the mountain. During those five days, the Marines carried the body of one of their brothers, PFC Wilford Lynn Donoho. Some of the recent conversations I’ve had dealt with this, but mostly they were debates about who was where when what happened. Nothing much was said about how this affected us.

After Lynn was killed, his Marine brothers carried him down the mountain with compassion, love, and respect. In a sense, they were his pallbearers and brought him home to his family. The family may never know this, but those Marines paid Lynn the highest possible honor, and they did so at great personal risk. They will live with this for the rest of their lives, but they should recall it with pride. Unfortunately, without the feedback they might otherwise have received, I’m not sure this will be the case. So, I’ve come to appreciate that, while the facts are important, so too are how they made us feel. Perhaps through these emotions the veterans and the families will be able to connect.

Much of the difficulty in communicating stems from the fact that veterans came back filled with conflicting emotions. Pride, shame, anger, regret, and sadness were among them, but perhaps the one that surprised us the most was homesickness. We were, to our dismay, homesick for Vietnam. Not homesick for the war, but for the others who were still there. A lot of us weren’t quite sure how we got back, or in fact, whether we deserved to be here.

Deserved or not, we’re here, and it seems that we now have an opportunity to do something we couldn’t do, or didn’t know how to do, back then. The Education Center at The Wall will give us a chance to pay our respects in a way that I hope will help the families of Vietnam veterans who died there as well as the veterans who didn’t. However, as I’m finding, even as we try to tell our stories, questions arise. How much of the story do I tell? What do families and friends really want to know? Am I even worthy of telling their stories?

PFC James Stingley‘s story is one that I found particularly difficult to tell. James was a young Marine from Durant Mississippi. He was a college graduate with a degree in accounting and at the time had a two-month-old daughter he would never see. Few of us knew any of this about James. He was a quiet guy, well liked by his fellow Marines, but apparently not one to talk much about his personal life.

James was killed on the morning of August 25, 1969, during a daylong firefight in the Hiep Duc Valley. Just about all of 2nd Battalion was similarly engaged that day. James was among a number of Marines killed, but he was in a different platoon, and I didn’t know him by name.

In the days prior to the 25th, our Battalion had been in almost constant combat. As we moved out that morning, we knew contact with the NVA was certain. James, fully aware of the danger, took his position with the point squad without hesitation. I can imagine him thinking, ‘I don’t really want to be here, but if it’s not me, it will be one of my friends’. As they moved through a tree line, the NVA opened up with mortars, RPGs, and heavy machine guns. He and two other Marines died in the initial volley.

Repeated air strikes and artillery failed to dislodge the NVA, and they kept the company pinned down until dark. At that point, we were out of ammunition and withdrew under cover of darkness. James and the other two Marines were left on the battlefield that night. We went back early the next morning, and under covering fire, several marines went into the open to bring back the Marines. I helped another Marine bring James back. I didn’t know who he was at the time. I don’t remember who the Marine was who helped me, and I don’t know who the Marines were who recovered the others. It didn’t seem important then, and as it usually happened, the choppers arrived, took away the dead and wounded, and we moved on.

Now I’m beginning to realize that there are a lot of stories like James Stingley’s and that the details are indeed important. James has a daughter somewhere who never knew him and may have no idea of the kind of man he was or what his fellow Marines did to make sure he got home. I didn’t known James, but I can still feel the weight of him.

I have gone to The Wall a number of times since that first visit. It’s a profound and emotional experience each time. On the first visit, my daughters were very young, but as they grew up, and we returned to The Wall, they started to realize how deeply these visits affected me and millions of others. Over time, they asked a lot of questions, and, I think, truly began to understand what was lost to the names on The Wall and their families. In the picture above, my daughter Susan is holding an old photo taken when I first arrived in Vietnam. Corporal Christopher John Ricetti, my radio operator, and Lance Corporal John Joseph Schmidt, one of my squad leaders, are on the left. I’m still working on their stories, but when I look at this picture, it reminds me that The Wall really can keep the memory of these names alive. If a weighty hunk of black granite can do that, I can only imagine what the Education Center will be capable of.

]]>

When the American public goes to great places where history is remembered, not everyone thinks about all the work behind the scenes. At places like our National Parks there is a lot of activity to keep everything looking good.

Washington, D.C. is a town with many memorials and statues remembering famous citizens ranging from President George Washington to the man who developed the counter rotating propulsion for ships, a Swedish immigrant named John Ericcson.

Who takes care of these memorials and monuments once constructed in Washington? The primary agency is the National Park Service. Their dedicated employees do the best they can with the staff and funding made available by Congress. Their funding is also augmented by nonprofit groups including the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund. VVMF also provides some highly respected expertise including engineering firms and geologists to review the actual structure from time to time.

Of interest is the recent visit by Objects Conservator Russell Bernabo. Russell was respected by Frederick Hart, the sculptor for the Three Servicemen Statue. Bernardo really understands how to maintain the metallurgy of statues using proper techniques and treatments such as Carnauba waxes.

A stitch in time saves nine is a good way to introduce the recent visit of Russell Bernabo to do some work. This is what he wrote after a visit in August:

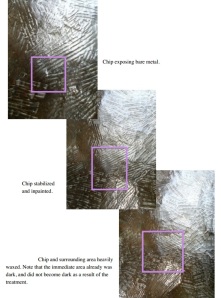

“Our routine maintenance to The Three Servicemen was completed this week with only one significant deviation from the usual wash, wax, corrosion intervention procedures. The area on the top of the base immediately below the proper right figure (machine gunner) had several very small areas of complete patina loss exposing the shiny core metal. These three chips were tiny but deep, as though a sharp object fell on the base. These chips were stabilized with Incralac to prevent the patina from peeling back, then toned to blend, and heavily waxed. This correction is a permanent repair, and we will have no further trouble from these mysterious chips. This might seem very inconsequential, but it is tiny dings such as these that spread into large losses, especially in this area that gets inevitable abrasion from visitors’ shoes.”

“Our routine maintenance to The Three Servicemen was completed this week with only one significant deviation from the usual wash, wax, corrosion intervention procedures. The area on the top of the base immediately below the proper right figure (machine gunner) had several very small areas of complete patina loss exposing the shiny core metal. These three chips were tiny but deep, as though a sharp object fell on the base. These chips were stabilized with Incralac to prevent the patina from peeling back, then toned to blend, and heavily waxed. This correction is a permanent repair, and we will have no further trouble from these mysterious chips. This might seem very inconsequential, but it is tiny dings such as these that spread into large losses, especially in this area that gets inevitable abrasion from visitors’ shoes.”

So, you see, taking care of statues is important and requires expertise. Preventing problems through early detection is a big deal. A few years ago it was a very big and expensive deal; VVMF had to spend over $250,000 to completely restore the statue. Since then we have had our own experts take care of this. We also have private contractors take care of the grass.

We are proud to take care of this place where America’s fallen are remembered.

]]>

On September 10, 2001 I was in Boston. Senators John McCain and John Kerry were attending an event at the State Street Bank. I was there to plead for help from both Senators about building the Education Center at The Wall. The CEO of State Street Corp., Marshall Carter, a decorated Marine, got me invited to make the pitch.

On September 10, 2001 I was in Boston. Senators John McCain and John Kerry were attending an event at the State Street Bank. I was there to plead for help from both Senators about building the Education Center at The Wall. The CEO of State Street Corp., Marshall Carter, a decorated Marine, got me invited to make the pitch.

At the time, legislation to build the Education Center was stalled. I needed Senators McCain and Kerry to weigh in and assist the sponsor of the bill, and I needed Senator Chuck Hagel to expedite hearings.

“Of course you can count on me,” said Senator McCain. Senator Kerry said about the same words. It was a long trip to get in front of these guys, but the mission was a success. These are both honorable men.

Senator McCain left that evening to get back to DC. That night I enjoyed a nice meal with Rick Lieb, another combat Marine officer from Vietnam and a generous donor to VVMF. I got a good night’s sleep.

Hailing a cab in rush hour is easy in Boston. My driver was a tall and easygoing man from Pakistan. He told me about his life growing up as the only Muslim in a rural New Jersey town. He enjoyed baseball, but could not eat hot dogs or drink beer as an observant Muslim. He laughed when I asked him how many beers he tried. “Most of them, sir, but I have cut way back.”

At Logan Airport the hijackers and I sat on the runway, in different planes. They had chosen aircraft heading to California instead of the Boston-DC shuttle; they needed a lot of fuel to explode when they hit the target of the World Trade Center.

When I got off the plane at 10 AM I saw about 30 people gasping looking at a small TV Screen. “A plane just hit the World Trade Center,” said a college aged woman in jeans and a Georgetown sweatshirt. As I looked I saw the other tower being hit.

“Terrorists” I said to her. As I said that a large explosion rang out. “I think they just hit the runway.” It was the Pentagon. Immediately there were sirens and announcements at National Airport. “Ladies and Gentlemen, please evacuate the airport due to a security issue. There will be law enforcement officers directing you when you exit”

I do not excel at following crowds. It was a four-mile walk to my office. I walked to the highway and a car stopped for me. A talkative woman pulled over and asked if I needed a ride.

She was nervous. “I work for Senator Ted Stevens. I am what you call an Eskimo, a member of the Tlingit Tribe. Oh gosh I am so nervous. I just started this job and I am late for work. Do you have any cigarettes?” Within minutes we were happily puffing away. I have since quit, thankfully.

After we lit up I said, “I think you picked a good day to be late. I will bet they close the Senate offices.”

Meanwhile there was drama on the radio as they announced that the plume of smoke we were seeing was the Pentagon on fire. The announcer said, “We are now getting reports of explosions throughout Washington. Armed Marines are being deployed to protect the Capitol.” The announcer was giving out bad information; sonic booms from military jets were causing chaos. It was a scene from Orson Wells’ War of the Worlds.

My ride let me off on Independence Avenue. I still had another mile. Another helpful Pakistani cab driver stopped to give me a ride. After ten minutes of sitting in the cab, he looked at me. “I think you would make better time walking, sir. No charge and good luck!”

Meanwhile my wife and staff had assumed the worst for me since media reported that the hijackers left from Logan Airport at about 9AM. Cell phones did not work.

The VVMF offices were on 15th Street near the White House. VVMF staff appeared happy to see me when I arrived after dodging police roadblocks and negotiating with various law enforcement officers.

I was stuck in DC for two nights. I ran into Ron Gibbs, a VMF Board Member from Chicago who was also at National Airport. Around 6 PM one thing was clear: we both needed a couple of drinks. We taxied to Georgetown where Humvees were on street corners. Soldiers with M16 rifles were nervously looking at the few people who were wandering around.

This was a very tough day for me, but a much tougher day for America.

]]>

Vietnam veteran and Wall Volunteer Jerry Martin joins VVMF staff in the Washington, D.C. office for our inaugural podcast. Jerry will serve as the host of Vietnam Voices in the coming months but first, we wanted to sit down and get to know him. Learn about Jerry and our new monthly series of podcasts.

In episodes to come, we’ll discuss the Vietnam War, The Wall and issues pertaining to all veterans. We openly welcome suggestions for new discussion topics and interview guests. Stay on the lookout for more from us in the future, and let us know what you think!

]]>

Excitement is building as people across the nation participate in the fundraising and photo gathering efforts for the Education Center at The Wall. I recently met with some donors and volunteers in Chicago for. Their generous support overwhelmed and inspired me to keep moving forward.

Excitement is building as people across the nation participate in the fundraising and photo gathering efforts for the Education Center at The Wall. I recently met with some donors and volunteers in Chicago for. Their generous support overwhelmed and inspired me to keep moving forward.

The International Brotherhood of Teamsters is well known, but not for everything that they do. The Teamsters have worked tirelessly to find jobs for returning veterans by expediting the process by which returning veterans can obtain Commercial Truck Driver licenses. Finding a job after completing a few years in the military is a crucial element to a smooth transition to civilian life.

The Teamsters Military Assistance Program has been led by Teamster Mick Yauger, a combat veteran of the 173rd Brigade in Vietnam. He is a gregarious, extroverted and dedicated man. Last week I was with him and a couple hundred people at the Chicago Hilton to raise money for the Education Center at The Wall.

At the benefit we auctioned off a Chicago Cubs jersey and baseball bat, a dinner at the Union Club and an autographed bottle of Honor Wine etched with Congressional Medal of Honor recipient Sammy Davis’s dog tag. The event was endorsed by Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel and Governor Pat Quinn. Colonel Sutherland, who was adviser to Adm. Mullen while Chairman of the Joint Chiefs, and who remains engaged in a nationwide effort to find jobs for veterans, made a $3000 donation in the auction for the bottle of Honor Wine. This heroic American has led soldiers in Iraq and lost some fine Americans fighting al Qaeda.

Medal of Honor Recipient Sammy Davis played “Shenandoah” on his harmonica as a tribute to a friend who fell in the Vietnam War. He auctioned the instrument. A man in the audience gave him $3000 for the instrument, but returned the harmonica to Sammy.

Congress recently passed H.R. 588, which allows donors to be recognized in the Center. Individuals and companies like ConocoPhillips, Time Warner, Spurs owner Peter Holt, Boeing and others who have made or will make million dollar donations will have their name displayed. One veteran I met will consider a million dollar gift.

It was clear that the veterans of OIF and OEF in attendance were excited and to know that the Education Center will also recognize their efforts. ”I will be there at the dedication to see Bill’s photograph. Every one of us, a million strong, will visit the Center,” said an emotional veteran who was wounded in Afghanistan. These 7,000 Americans who have died in the current conflicts will have their photos displayed hourly at the Education Center.

The Center will celebrate America’s Legacy of Service. The primary exhibits will show some of the 400,000 items left at The Wall, the history of the war in Vietnam and the photos of the fallen from Vietnam. We now have over 32,000 photos thanks to the efforts nationwide of people like Janna Hoene, who got another eight photographs last week from the area of Hemet, Calif.

The grassroots support is growing nationwide at a significant pace. Excitement and anticipation surrounding the Education Center are building. In Times Square, an incredibly moving advertisement is on display that shows two heroes whose photos will one day be displayed in the Center. Volunteers from Chicago to Hawaii to San Diego to Orlando are joined by America’s most respected citizens including the leadership of both parties in Congress, former Chairmen of the Joint Chiefs, the Obama Administration and others.

The time to complete the mission is now to complete. We are planning a groundbreaking in 2015. We are raising money. Will you be a part of this? The Center will celebrate the service of those who risked their lives for your freedom. From Bunker Hill to Baghdad, they will not be forgotten.

]]>

But Stephanie had something of a guardian angel in her high school classmate Gaylyn Shay. Gaylyn had heard that The Wall That Heals was coming to their hometown of Albany, Ore. So she called Stephanie and told her she had to go and what’s more, she ought to participate in the Faces Never Forgotten campaign, a project that aims to collect a photo for each of the 58,286 names on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial. When Stephanie explained that she didn’t really have anything to submit, Gaylyn got down to work.

Previously Gaylyn had hired a young homeless man, Mike George, to help with her photography business. She told him that if he learned how to restore old photographs, he would always have a job with her. Gaylyn and Mike worked together on the photo, trying to fill in the missing parts. They used pictures of William’s father and grandfather to try and recreate his face.

“She kept saying, ‘Well the nose is almost right,’” Gaylyn said. “It was frustrating. But so important.”

Stephanie realized the local newspaper, the Democrat Herald, might have a photo of William in their archives and so she asked Gaylyn to investigate. After some digging, Gaylyn found it. But since the photo was from a newspaper, it was essentially a bunch of very small black dots. Scanners and Photoshop cannot pick up those types of images so Gaylyn and Mike had to get “artistic.”

After about 80 hours of work, the two had a beautiful photo of William. Stephanie didn’t know they had found the newspaper photo to work off of; when she came to The Wall That Heals event on August 8, she was shocked to be given the restored photo of her brother. The photo was then submitted to VVMF’s Virtual Wall of Faces, where it will live forever online and eventually in the Education Center at The Wall.

Gaylyn says she now plans to find and restore the photos of two of her other high school classmates who also lost their brothers in the Vietnam War.

“This needs to be done to honor them,” Gaylyn said. “These were people, not just casualties or numbers. You can see that in their faces.”

]]>

Last week I was in Washington DC for the Mission Possible workshop conducted by Model Classroom and the Pearson Foundation. It was a thought provoking and emotional experience, including a day at the Vietnam Veterans Memorial listening to veterans share their stories.

Last week I was in Washington DC for the Mission Possible workshop conducted by Model Classroom and the Pearson Foundation. It was a thought provoking and emotional experience, including a day at the Vietnam Veterans Memorial listening to veterans share their stories.

I asked Leann about her cousin and she had already located his name on The Wall using the app from the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund. The app allows you to search for names on the wall by name, hometown, state, etc. Her cousin’s name is Elmer D Lauck. I took a picture of her screen showing the location of his name and later on our tour I took a picture of his name on The Wall.

These pictures are for Leann and her family. Today as I visited it was peaceful. There was a light breeze and in the shade of the Cottonwood the only sound was a slight rustling of leaves from above. Let them know that he is remembered and honored.

]]>

Steve Delp

By Col. Steve Delp

Ann and Steve Delp represented the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund at the annual reunion of the 4th Infantry Division Association in Columbus, Georgia, July 17 through 20, where they joined several hundred 4th Division veterans and their families. The emphasis of their attendance was to inform the members of the status of the Education Center to be built on the Mall in Washington, DC, and the continuing need for donations to make the Center a reality. They also briefed on Faces Never Forgotten, the need for pictures of those whose names are on The Wall, as those pictures will become a significant part of the Center. Thus far, VVMF has obtained pictures of over 32,000 of the 58,000 names on the Wall. In addition, they presented briefings and brochures from the Library of Congress’ Veterans History Project, a major effort to create video interviews of military veterans from around the country. The project has created some 50,000 such stories, and the Library is looking to create many thousands more.

We believe the VVMF representation was a major success as most if not all members stopped by to discuss the Center and Faces Never Forgotten, as well as to share experiences, mostly in Vietnam. The discussions rekindled memories, some happy and entertaining, as well as the remembrance of the sadness of war. They also pointed out a concern shared by most veterans’ organizations that the membership, largely from the Vietnam timeframe, is beginning to show its age. The 4ID  leadership made it clear that their main task is to bring recent veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan into the association in order to share their experiences as well as to provide a new, and younger, outlook for the organization. The VVMF shares this concern as seen in our plan to represent those GWOT personnel in the Education Center until the organizations from those conflicts obtain the right to have their own memorials to express their military history.

leadership made it clear that their main task is to bring recent veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan into the association in order to share their experiences as well as to provide a new, and younger, outlook for the organization. The VVMF shares this concern as seen in our plan to represent those GWOT personnel in the Education Center until the organizations from those conflicts obtain the right to have their own memorials to express their military history.

While we met so many wonderful veterans and their families, one person in particular stands out in our minds. Her name is Susan McLean, and she was a Red Cross Donut Dolly in Vietnam during 1970 and ’71. She is now a teacher and youth activist in Florida. Throughout the reunion she always demonstrated the warm, bright, fun loving personality we came to expect from all who served as “Dollies” in Vietnam. Thanks, Susan, and don’t ever change!

It was a great week, and we look forward to working with the fine folks of the 4ID Association in the future, as well as joining many other organizations at their upcoming reunions.

]]>

Before and after cleaning

The Three Servicemen Statue stands at the treeline of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, eternally watching over the 58,286 names of those who died in the Vietnam War. And just as The Wall requires regular cleaning and maintenance, so too, does the Three Servicemen Statue need special care.

As the statue is exposed to pollen, insects and pollution, it receives preventative conservation cleaning four times a year paid for by VVMF. But this June, Objects Conservator Russell Bernabo noticed the statue needed a little extra elbow grease.

When rainwater washes over the base of the statue, it brings with it mulch debris. As the water evaporates, the mulch embeds into the wax.

“That part needed a more aggressive cleaning,” Bernabo said.

It took three whole days for Bernabo to clean the piece, designed by the late American sculptor Frederick Hart. Bernabo is an expert in caring for Hart’s work.

“I like interacting with the guests [when I work on the Three Servicemen Statue],” Bernabo said. “They appreciate that VVMF wants to take care of it. We all take this job very seriously.”

The statue was unveiled in 1984, two years after The Wall’s completion.

]]>